If you are sick of hearing about Donald Trump, now is the time to stop reading. Indeed by the time you are reading this, it may be that Trump has disappeared from history, returned to the world of reality TV, or led a fascist overthrow of American democracy. But at the time I’m writing, he’s still contending for the Republican nomination for US president.

Unlike most of my friends, I’m not sick of hearing about Donald Trump. In fact I find him fascinating and weirdly, slightly sympathetic. Perhaps it’s because I like to try to understand the psychology of evil. My favourite Little Britain sketch is the Russian babysitter “You want babysitter? You call my cousin Boris: is very bad man… but in heart is try to do good!”; and my favourite Game of Thrones character is the Hound. Also, I find fascinating Albert Speer’s description of his first meetings with Hitler, in which the 20th Century’s most diabolical historical figure is initially shy and tentative about sharing his amateur views of architecture with a professional.

But, actually, I think that Trump is quite unlike all three of those characters, and in a certain respect, he’s more like me. That respect is a strong desire for the approval of others. Now, the trouble with approval is that it’s like the cocaine of social interaction - the pleasure is strong but brief, and leaves you disappointed. When I’m working on an academic paper or a blog post, I tend to try to motivate myself by thinking about the positive reaction I will get from other people when they read it. But it can take years to develop an academic paper to completion, and when it is completed, the pleasure I feel at getting it published lasts only a few days. Moreover, after those days have passed, there’s a comedown as I realise that now I have to start working on the next paper, and my next hit of approval may not come for a year or more! No surprise then, that I suffer from procrastination - difficulty motivating myself during the middle stages of a large project.

I’ve learned that, in order to get by in the world, I have to have a more diverse set of motivators, so I consciously try to focus on motivations other than approval. One that works well (especially well for academic work) is the intellectual pleasure involved in solving or partially solving a puzzle, and in writing well, and I can take pleasure in those things even if nobody sees the finished product.

But what would it be like for someone who for some reason wasn’t able to take pleasure in either of those things, or anything else, someone whose only source of gratification was approval? That is how you end up a narcissist, and as many amateur psychiatrists have remarked, Donald Trump seems to be a textbook case of Narcissistic Personality Disorder (no professionals will comment on this, because it would be unprofessional of them). So, here’s what I think it’s like for Donald: imagine that you can only take pleasure from approval; that makes your life pretty empty. You are so terrified of not feeling approval that you develop an elaborate fantasy according to which pretty much everything you do deserves the rapturous attention of others, and you do everything you can to get people around you to participate in this fantasy. Pretty soon you become the prisoner of this fantasy - you rethink the world in its terms, for example, by attributing malicious motives to people who won’t play along with it.

I think I can imagine what it must be like for Trump, partly by extrapolating from my own personality traits, and partly because I’ve known a couple of narcissists myself (sgain, this is my own amateur diagnosis). One was an undergraduate student of mine. He was a dreadful student - came to class unprepared - wasted time with aggressive irrelevant questions - and when it came time to hand in his essay, predictably it was barely relevant to the course. I gave him a high fail, because his essay was at least articulate.

The weirdness began when this guy showed up in my office wanting to dispute his grade. He was shocked that he had failed - he was normally an A student (he said). The failing grade I had given him was final for the essay, I said, but not a disaster for the course overall - he could easily make it up in later assessment and I would be very happy to help him. How could he do it? Well, I asked, how had he approached the set readings? One thing that had struck me is that he hadn’t referred to them. “Oh, I never bother with the readings, I always find that my essays are so much better when I just say what I think.”

“Really?” I asked. How was this strategy working in the other courses he was doing? Just fine; he had written a fantastic essay for his history course. What grade had it got? A C-, but what was because his history lecturer hated him, unlike me - I was clearly on his side despite the misunderstanding over the philosophy essay, which I would surely now regrade since I now understood what he was up to.

It was at this point that I realised that this young man was deeply deluded in a way that was beyond my power to help. As gently as I could, I said that I thought that he was a very able student and that he wasn’t getting the grades he deserved because he wasn’t preparing properly for class or for assessments. I suggested that he just try doing the readings and see if it helped his grades. As I said this, it seemed to me that, for just an instant, the mask slipped and I saw in his expression his terror at the realisation that contrary to what he had believed, he was consistently writing very poor essays - that his low grades were due not to malice or misunderstanding, but to his own unwillingness to do what his lecturers expected of him. I got to see this, I think, only because I had been extremely patient and tolerant. But even so, it lasted only an instant. If I wouldn’t regrade his he essay, he said, how could he take matters further? He could see my head of department. I said. I never saw this student again.

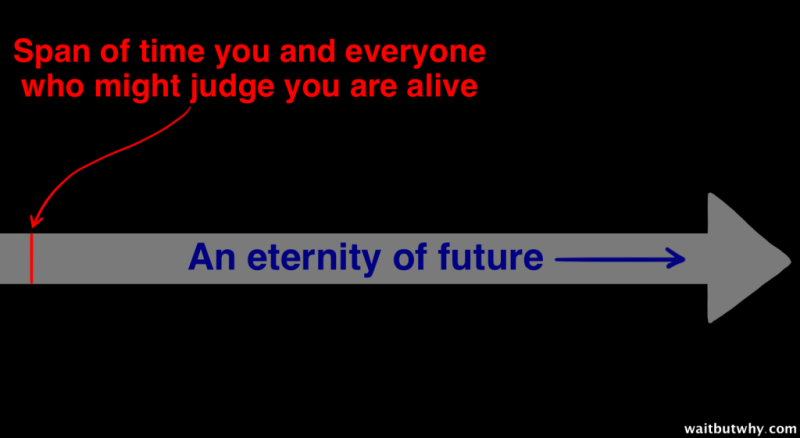

This student came across, superficially, as almost unbelievably arrogant and insensitive, but (I think) inside he was lonely and scared. His weird self-beliefs were driven, not by moral failing, but by the fear that the world is really an empty and meaningless place; that, sub specie aeternitatis, nothing is gained by success and nothing lost by failure. So with Donald Trump. I don’t know the man, but I imagine that his inner life is a losing battle with horrifying existential angst (or, technically, with nausea - it’s the uncaringness of the universe, rather than the radical freedom of agency, that upsets him I think). And so, every time I see him incoherently blustering about what a “winner” he, or attacking various obviously innocent scapegoats, I just think about what must be driving him to that and feel sorry for him.

Here’s a nice illustration, courtesy of Tim Urban of waitbutwhy of what causes Donald Trump unbearable existential nausea:

Since I’m already mentioned Hitler, I’ll spare a few words for comparisons between him and Trump. I think they are very different personalities. True, both are poisonous bigots and demagogues, but beyond that they have little in common. Trump, typically for a narcissist, is way too wrapped up in himself to have any understanding of how he appears to anyone else. To do that he would have to run the risk of thinking that he comes across badly, that he fails to win approval. Hitler, on the other hand, from all reports, had a chameleon-like ability to be all things to all people. We tend to think of newsreel footage of Hitler in military uniform working his audience into a frenzy (how like a Trump rally!) but he could also don a sober blue suit and speak modestly to audiences of mixed political persausions about the need to unify against communism. This is the guy who persuaded the political classes of both France and the UK that he posed them no military threat for years while rearming with the explicit intention of waging a war of choice!

Hitler was dangerous because he had vicious intentions and was capable of putting himself into the shoes of others to simulate and predict how they would react to him. Trump has far too little understanding of those around him to manipulate them, and his only intention is to attract an approving audience by saying whatever his supporters seem to like. As a US president, my guess is that he would be the pawn and mouthpiece of his advisors, much as George W Bush was before him.